By Anand Venigalla

Staff Writer

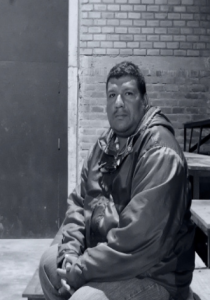

Associate Professor of History, Willie Hiatt spent his fall 2017 sabbatical working on an oral history project in Peru. He interviewed between 75 and 100 individuals about the blackouts that occurred in Peru during the Shining Path period in 1980-2000, particularly those that took place during 1982-1992.

Hiatt chose the oral history format in order to give a better picture of the personal experiences people had. “Oral history can provide insights into macro-and micro-level engagement with technology that differs substantially from ethnographic observation [scientific descriptions of peoples and cultures with their customs, habits, and mutual differences] and archival sources. To be sure, blackouts were complex technological events, but they also were social crises, police and military challenges, economic and political emergencies, and often life-and-death matters,” Hiatt said.

Interviews enabled individuals to articulate their responses to nationwide attacks on electrical grids as well as the accompanying loss of traffic lights, gas stations, elevators, water pumps, washing machines, televisions, blenders, and many other technologies that modern societies take for granted. “My research remains attentive to the fact that oral history interviews are processes of remembering, and as such, these retrospective accounts must be subjected to critical discourse analysis,” Hiatt said.

Oral history narratives can be rich sources of documentary evidence and, according to Hiatt, can make an important contribution to our understanding of how people engage, understand, adopt, and adapt technology. “Interviews will allow respondents to tell personal stories that raise larger historical questions and illuminate shifting national narratives,” Hiatt said. Hiatt has written a book, “The Rarefied Air of the Modern: Airplanes and Technological Modernity in the Andes,” also based in Peru. This led him to further explore the role of technology in Peru. “I began to consider a project on the history of electricity. Electricity arrived in Peru in the late nineteenth, early twentieth century, and I did quite a bit of archival research on that, and I am still going to explore that and possibly incorporate that into this current project,” Hiatt said.

Oral history provided Hiatt an opportunity to explore territory that he previously did not explore. “Between 1982 and 1992 mostly, blackouts due to the destruction of these electrical towers became a way of life in Lima, and just about everybody regardless of your profession, your socioeconomic level, where you lived in Lima, whether you were in one of the poor marginal areas or in a more affluent area, everyone experienced these blackouts and had a personal account, personal memories of what they did during these power outages. And so I began to think about doing oral history for the first time.” The research he did for his first book was exclusively archival, including newspaper articles, congressional documents, military documents, official reports, and magazine articles. This project consisted of interviews.

Hiatt interviewed engineers and artists, doctors, people in the poorer areas, and teachers who taught night school. The power outages almost always happened between 6 p.m. and 8 p.m., which had a big impact on classes that took place at night. He also talked to several people who were in the arts, including at least two novelists about their work and their experiences. “It was an amazing experience to travel all over Lima and to see lots of different people from different socioeconomic levels from different professions to hear their stories,” Hiatt said.

“I was really impressed that Peruvians were willing to open up to an academic from the United States and to tell their stories. Often I would get names of potential informants or interview subjects from friends of friends and I would only have a cell phone number, so I would often call them up and I would have 45 seconds or a minute to introduce myself, to tell them what my project was about and to ask if they would be willing to meet with me to give me their testimony or to share their memories. The great majority of people who I asked to interview accepted. Some of them were just amazing. Even people who didn’t necessarily have a higher education could be very articulate in discussing and thinking about the impact of the blackouts on their lives,” he said.

The intent of the blackouts, according to Professor Hiatt, was to sow chaos and to destroy the bourgeois regime; but while there was fear and anxiety about how to deal with these blackouts, the blackouts had interesting cultural and social effects on Peru. “A whole culture of coping with blackouts emerged, candles became a staple in just about every Peruvian household, some of the wealthier families and many businesses had small electrical generators, and the sound, the roar of those generators was what many of those informants remembered from that period. Peruvians were quite ingenious in their response in some ways; a little informal business emerged where people would use a car battery to supply a television or maybe small appliances with the house,” Hiatt said.

For Hiatt, the stories of the Peruvian Shining Path period have much to teach us about the role of technology in society. “It shows you the role that technology plays in both bringing people together but also kind of isolating people,” he said. “One really interesting description of the blackouts was that it brought family members in their households together because people had to stop watching TV. It forced people to talk and to have family conversations again. That was before even cell phones and iPads and computers, so we’re even more isolated in many ways today. And so in this case, the blackouts brought people together. In another sense, it also brought people together because this was a common experience based on technology that everybody, whether you were in a poorer section or a wealthier section, experienced.”

Although he is back on campus for the spring semester, Hiatt is still working on the project. “I have a conference in Belfast in April where I will be presenting the first findings of this project. I’m not completely finished with all the interviews, so I will return to Peru in June and July to continue,” he said. In addition, Hiatt intends to turn his oral histories into a book.

This semester, Hiatt is teaching HIS 304: World History, 1750-Present (Honors), HIS 190: Globalization and Latin American Film, and HIS 599: Latin American Intellectuals.

Jeanie Attie, chair of the history department, has found Hiatt’s efforts to be of educational value to students. “Professor Hiatt’s research on Peruvian history and his use of a wide variety of sources (including interviews, films, fiction) have provided his students with unique understandings about how ordinary citizens experience historical change and how past events shape the present,” she said. She added that Hiatt “has always been committed to teaching his students how history is done and I am sure they will be intrigued to learn more about oral histories.”

“This is an ongoing project,” Hiatt said. “Although I completed most of the research during my sabbatical, I will continue different aspects of the project for years to come.”

Be First to Comment